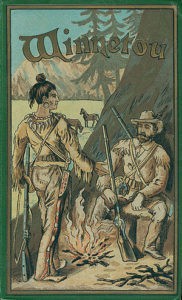

We’ve come a long way since German novelist Karl May (1842-1912) wrote a series of books romanticizing American Indians, without ever having met one or even having visited North America. His books (the Westerns feature Winnetou and Old Shatterhand, and Adolph Hitler was a fan) sold 200 million copies worldwide, and remain popular to this day. Which means that to this day, Germans hold events where people dress up as his characters (complete with feathers in their hair and fake deerskin dresses), which appalls many North Americans. The legacy of this inauthenticity and stereotyping has been long-lasting.

These days, fiction writers cannot write about someone of a different culture, skin color, religion, disability or sexual preference without hiring a “sensitivity reader” (one for each of the above categories, if multiple characters are involved) – generally at their own expense, even if it is the publisher insisting on it before agreeing to publish the book. The given reason is for more authenticity and respect (a good thing), while a secondary reason is to cover their butts when media controversy by the politically correct (PC) brews.

It goes to say this new trend (and the cost of it being put on authors) puts a chill on the notion of writing about characters other than oneself, though this is surely not what the PC police intend.

But lest you think I am going to launch into an anti-PC rant, guess what? Due to a recent sensitivity-reader experience that has won me over, I am not. I will relate that story in a minute.

Yes, I think the sensitivity-reader demand sometimes goes over the top, with unintended consequences, and I also think that one so-called sensitivity reader can hardly represent an entire community of whatevers. If someone wants to pay me to vet a white character, does my opinion reflect that of all white people?

More to the point, a fiction writer’s job is to make up characters: a full, rich cast of characters. Preferably one that reflects the diversity of the real world. How boring would a novel be if every character in it looked like me, a middle-aged white female? I have been writing books for teenagers (and they are particularly popular with boys) for 20 years. I am not a teenager. I am not a boy. Some of my characters have not been white.

But, here is my recent experience. I just wrote a novel with a bad guy who happens to be a Korean who has moved to Canada. He speaks in halting, imperfect English. So I was told to get a sensitivity reader who is Korean (and pay for him or her myself).

I asked around, and found a fellow novelist born in South Korea who grew up partly in Canada. I won’t name her for now, but she generously offered to be my sensitivity reader for free. (Kindness still exists in the world.)

It took me most of an afternoon to go through my 55,000-word novel to cut and paste the 2,000 words’ worth of antagonist Mr. Kim’s dialogue into a document for my sensitivity reader.

She read them aloud to her family over the holidays. They all agreed the character sounded Chinese, which prompted a lively discussion amongst them as to what constitutes a Korean vs. Chinese version of halting English. Then she translated the dialogue into Korean, and had a bilingual Canadian-Korean translate them back to her. This provided much of her feedback to me – no small task on her part. In fact, it was above-and-beyond generous (especially since it involved a bad guy😊).

In a phone chat, she then explained all this, suggested many word changes, and emphasized how much Koreans gesture, which prompted me to work that into my scenes. She also explained how Koreans address one another. They avoid the word “you,” which means the sentence, “You buy that sandwich” should be changed to, “Buy that sandwich.” And to achieve Mr. Kim’s lack of fluency with English, she suggested I eliminate plurals and -ing words, which meant changing a sentence such as, “I am making sandwiches” to “I am make sandwich.”

She did all this for the love of authenticity, and she did it with full understanding of how a novel needs a full cast of characters, including a bad guy. (Not all Koreans in this novel are bad, by the way.) She understood that how not working with a sensitivity reader would have meant that my first pass at the dialogue (and lack of gestures) would feel unauthentic to many readers. Okay, not many readers, but some readers.

Just as Karl May’s work continues to offend (and stereotype) some people to this day. Because he didn’t know, didn’t care. Nor did his readers.

But that was then and this is now. A “now” I’m okay with. Well, almost.

Interesting article, Pam. Thank you for writing it. I just wish I could have shared it with my social network.

What’s wrong with Karl May’s books? I love Karl May’s Westerns. I accidentally found them in a public library in northern England when I was a boy and started reading them. They opened up my imagination. I’ve heard before that Adolf Hitler liked them, and if that’s true, then he obviously had good taste in popular literature.

I know full well that it’s just fiction. That’s why I like it. It’s enjoyable partly because of the romanticisation and stereotyping. Fiction is supposed to be bit ‘unreal’. If fiction had to be faithful to reality, it wouldn’t be fiction, and whatever it would be, it would be very boring.

If I want to know about real Red Indians…sorry…American Indians….sorry, Amerindians….sorry, Native Americans…I’ll read a non-fiction book about them, or a more historically accurate fiction book.

I don’t see the issue. I think this is just people who are aggressively sanctimonious and want to look for reasons to be offended. These are horrible people who are sucking all the fun and colour out of life and want to turn us all into drones. I very much doubt any real American Indians…sorry….Native Americans….or whatever they’re called….are genuinely offended in the least by Karl May, assuming they’ve even heard of him.